Supporting South Asian Teen Mental Health

Parents mourn the death of thirteen-year-old Zaheid Ali, a sad testament to the struggle of British South-Asian teenagers

Please note the following content may be disturbing to readers. The article concerns teenage suicide and mental health.

Zaheid Ali fell into the Thames on the 20th of April. The City of London police has released a statement declaring the death as not suspicious, however, a series of alarming tweets on Zaheids social media shows a strong indication that Zaheid was struggling with mental health.

The student of Global Ark Academy, who had embarked a stop early from his regular bus stop, was last seen with a friend and reported missing on the April 20th.

On the 28th of April, his body was retrieved from the River Thames and identified by his parents. His death is being mourned and commemorated by his family and school.

Zaheids’ cause of death has yet to be picked up by mainstream media, as an inquest currently ongoing.

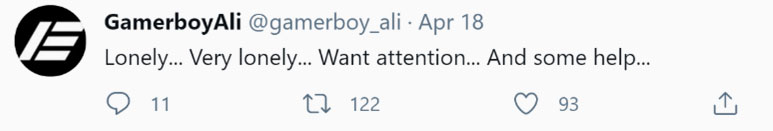

The burning question around Asian mental health reveals teenagers are more likely to turn to online platforms for help and support instead of family and friends. The story of Zaheids life is a testament to the struggles young people cope with daily.

Journalist Judy Farah explained her experience of studying mental health, “For a large part, people really don’t want to end their lives. They just want to end whatever pain they are in at that moment.” She continued, “Most think no one will miss them or ‘be better off without them, but nothing could be further from the truth.”

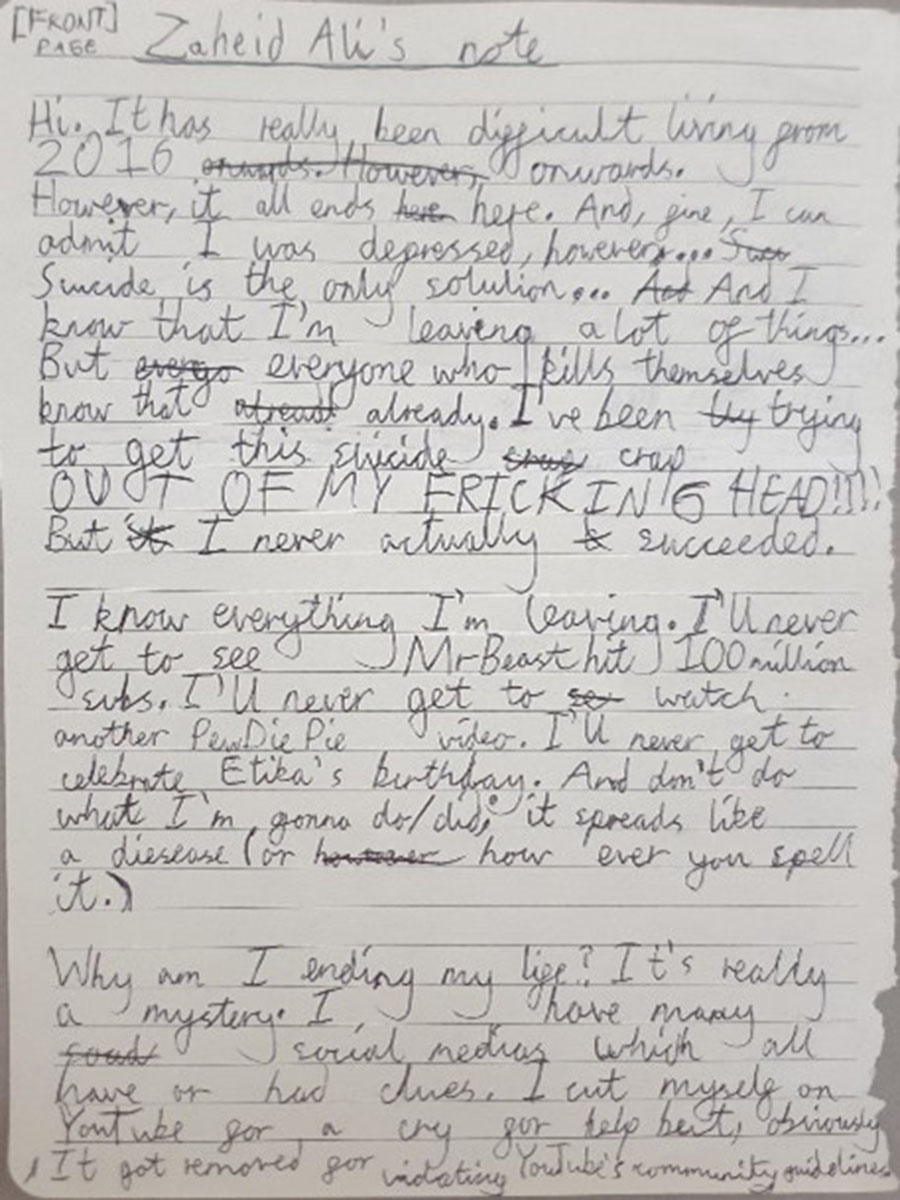

Like many other young people, Zaheid chose online platforms to call out for help. A suicide note was uploaded to his Twitter account, days before he fell into the Thames.

“Why am I ending my life?” he asked, terming the reason a “mystery” he stated, “I’ve had many social media, and all have had clues as a cry for help.”

The suicide note explained living had been difficult for Zaheid since eight-years-old.

He marked his struggles with coming to terms with depression and admits he had tried several times to get suicidal thoughts out of his head but never succeeded.

He pleads to anyone reading the note never to do what he did because it spreads like a “disease”.

A report published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in the UK stated, “images or talking about self-harm on social media can be a way to communicate distress, to share journeys of recovery, and to provide support and information to others.”

The mental health ‘Time to Change’ campaign has identified that mental health is stigmatised in the South-Asian community and discussed how shame and fear of others finding out are key reasons it is such a taboo topic, therefore more accessible for teens to share their journey online instead of in person.

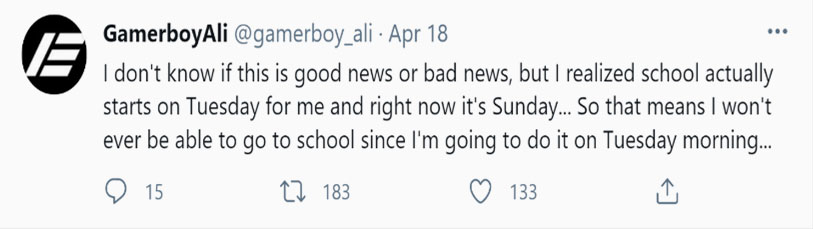

Zaheids attempt for help continued in the days leading up to his death.

Zaheid uploaded regularly on a Youtube page, which posted meme and gaming content. In November 2020, Zaheid posted a short video of getting lost in London with a friend and admiring London’s tallest skyscraper, the Shard. He can be heard laughing heartedly and making jokes stating, “this is definitely a post for YouTube.”

Five months later, Zaheid posted a short video counting down the days until he would attempt to take his own life.

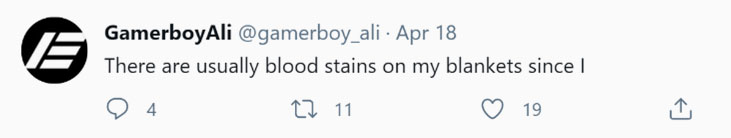

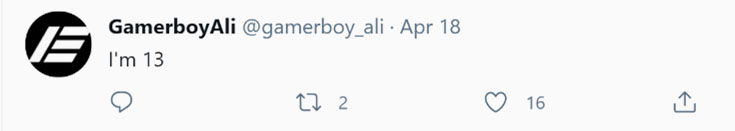

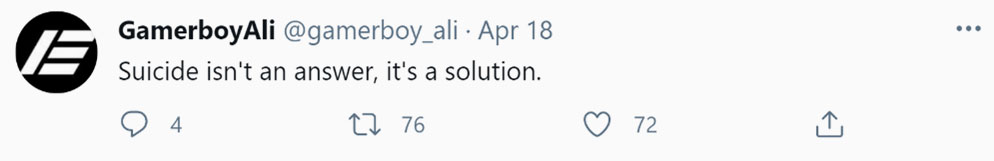

On April 18th Zaheid tweeted about cutting himself:

He later tweeted about suicide.

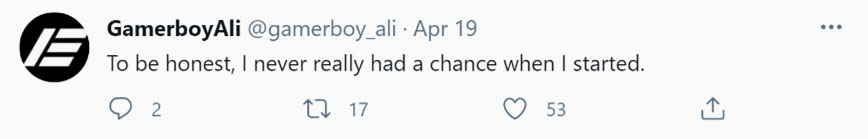

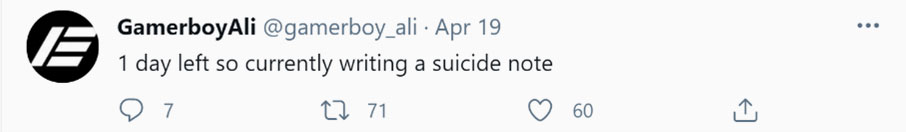

On April 19th Zaheid wrote his suicide note.

After uploading his suicide note, he tweeted a countdown.

The taboo on mental health may stray teenagers away from getting the help they need. The ONS report stated, “Some online imagery can glorify, sensationalise, and normalise self-harm.”

Places of support can be quickly turned into a sinister horrifying web of hate.

Followers spreading positive comments in response to suicidal posts are trolled with hostile and abusive responses such as “laughing at you.” In an attempt to share suicidal thoughts, a follower was cruelly and unsympathetically told suicide was “shi**y and dumb.”

Even though social media platforms have measures in place, including flagging words like ‘suicide’ and self-harm posts, displaying a disclaimer before sensitive content and a pop-up box with information on where to find help, critics have strongly advised these measures are not enough.

The biggest challenge flagged is social media algorithms programmed to show viewers images of the same content, even if the posts are self-harm and suicide.

This means young people are assaulted with gruesome and dark suicidal content repeatedly, unknowingly falling into a vicious spiral, negatively impacting mental health.

The taboo on mental health in the South-Asian community is a way of thinking that has been adopted for generations, with each brought up avoiding emotions.

Even though mental health is more talked about, the lack of understanding in the Asian community may lead teenagers to turn to role models who have been through the same.

Zaheids suicide note mentioned the things he was leaving behind, including celebrating late Youtuber ‘Etikas’ birthday. Youtuber Etika took his life on June 19th, 2019, after falling into the East River in New York and uploading an apology video to fans on social media before his suicide.

Judy Farah explained, “Bridges are an attraction for someone considering ending their life. They’ve heard of other people doing it, and it seems like a quick and easy way” she then explains, “A person hits the water at 75 miles per hour, and all their bones are crushed.”

The last lines of Zaheids suicide letter were dedicated to Ro Ro-Chan, a fourteen-year-old Japanese schoolgirl who live-streamed her death, jumping off a 13th storey ledge on November 24th 2013.

The death received little coverage or widespread attention beyond local news until 2019, a Japanese rock band Shinsei Kamattechan released an animated music video, “Ruru’s Suicide Show.”

Her death became popular in 2019, and sadly, a Tik-Tok Anime trend for those who did not know what the song was about.

The chorus of the controversial song, “The Citys Bluetooth destroyed me”, was crossed out in Zaheids note.

The term represents how addiction to the internet can break a person from socialising and form a depressed and unstimulated mindset, which may slowly lead to breakdown: a metaphor for destroying and taking over younger generation lives.

One in seven young people in the UK self-harm, and teenage suicide statistics are quickly rising.

The death of a talented, unique and precious son, brother and friend is a tragedy that will leave a permanent hole in the hearts of his family and friends.

The step towards understanding our young people is changing the way we think about mental health, our upbringing and lack of education.

With seminars, classes, and tools to understand the taboo on mental health, we can start to hear the plea of our young people and support them during their struggles.

We can do our best to keep them safe from a cruel online world, where any support or kindness was over-weighted by hatred and darkness.

Zaheids’ last Twitter post was “Fast.”

In the morning, he had woken up to get ready for school and checked the time at 6:57 am, almost 7 am.

At 8 am, he fell into the dark, freezing waters of the Thames.

Zaheids death will not be used to glorify suicide because he himself urged others not to cut themselves, not to self-harm.

In his death, his moments of anguish, the darkness swarming in his mind too chaotic and painful to let him continue, he left this world hoping no one would have to go through what he did.

Our deepest condolences and prayers are with Zaheids family. We ask our readers to be respectful of the beautiful life lost.

As displayed, mental health is a serious matter, often quickly overlooked in the South-Asian community. We urge and encourage people not to shy away from these matters and be more open and supportive towards young people struggling with mental health issues. It is time for us to change these taboos in our community and to help save more lives.

If you are a young person struggling, please visit:

- YoungMinds – children and young people’s mental health charity

- For children and young people | Mind, the mental health charity – help for mental health problems

- Teenage Mental Health | Child and Adolescent Mental Health Support and Therapy Ipswich

If you are an adult struggling, please visit

- Get Started (betterhelp.com)

- Oxfam GB | leading UK charity fighting global poverty

- Find a Therapist | Book Therapy Online (harleytherapy.com)

- Get help from a mental health charity – NHS (www.nhs.uk)

- Where to get urgent help for mental health – NHS (www.nhs.uk)

If you are worried about the mental health of a teenager, please visit

For daily positive morning affirmations, follow @AsianaTV for positivity and mental health updates.

Get Social